A Dimension Is A Measurement Written As A

Onlines

Mar 16, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

- A Dimension Is A Measurement Written As A

- Table of Contents

- A Dimension is a Measurement Written as a… What? Understanding Dimensions in Various Contexts

- Dimensions in Physics: Beyond Length, Width, and Height

- Understanding the Measurement Aspect: Scalars, Vectors, and Tensors

- Dimensions in Mathematics: Abstract Spaces and Geometries

- Manifolds and Topology: Beyond Euclidean Spaces

- Dimensions in Computer Graphics and Data Visualization: Representing Information

- Fractal Dimensions: Measuring Irregularity

- Dimensions in Other Contexts: A Broader Perspective

- Conclusion: A Multifaceted Concept

- Latest Posts

- Latest Posts

- Related Post

A Dimension is a Measurement Written as a… What? Understanding Dimensions in Various Contexts

The statement "a dimension is a measurement written as a…" is deliberately incomplete, designed to spark curiosity and delve into the multifaceted nature of dimensions. The concept of a dimension transcends simple numerical representation; it's a fundamental concept influencing various fields, from physics and mathematics to computer graphics and even philosophy. This article aims to clarify the meaning of "dimension" across these disciplines, highlighting its diverse interpretations and practical applications.

Dimensions in Physics: Beyond Length, Width, and Height

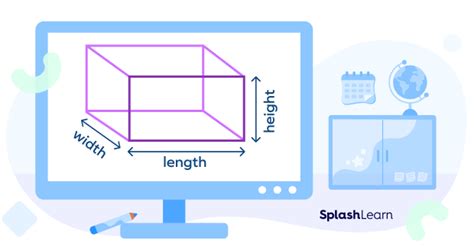

In physics, the most readily understood dimensions are the three spatial dimensions: length, width, and height. These define an object's position and extent within three-dimensional space. We experience and navigate this space intuitively. A measurement written as (x, y, z) coordinates represents a point in this 3D space, where x, y, and z are the measurements along each respective axis.

However, the physical universe is more complex than just spatial dimensions. Time, often considered the fourth dimension, is inextricably linked to spatial dimensions within the framework of spacetime. Einstein's theory of relativity unified space and time into a four-dimensional continuum, demonstrating that time is not absolute but relative to the observer's motion and gravitational field. A measurement in spacetime might be represented as (x, y, z, t), where 't' represents a temporal coordinate.

Beyond spacetime, physicists explore higher dimensions in various theoretical frameworks. String theory, for example, postulates that the universe has ten or eleven dimensions, most of which are compactified or curled up at scales too small to be directly observed. These extra dimensions are mathematically necessary to reconcile quantum mechanics with general relativity and potentially explain fundamental forces and particles. While we can't directly "measure" these extra dimensions in the same way we measure length, their existence is inferred from mathematical models and their effects on observable phenomena. Their representation is highly abstract and mathematical, often involving complex geometrical constructs beyond simple coordinate systems.

Understanding the Measurement Aspect: Scalars, Vectors, and Tensors

The way a dimension is "written as a…" depends on the type of measurement.

-

Scalars: These are single numbers representing a magnitude without direction. Examples include temperature, mass, and energy. A scalar measurement of temperature, for instance, is simply a number (e.g., 25°C) – a single dimension.

-

Vectors: Vectors possess both magnitude and direction. A displacement vector in 3D space is written as (x, y, z), where x, y, and z represent the components along each axis. Each component is a scalar measurement, but their combination describes a directed quantity. Thus, a vector can be considered a multi-dimensional representation.

-

Tensors: Tensors are generalizations of vectors and scalars, capable of representing more complex physical quantities with multiple indices. Stress tensors, for example, describe the internal forces within a material, requiring nine independent measurements to specify completely in three dimensions. The “measurement” here is a matrix of values representing the force components along different axes.

Dimensions in Mathematics: Abstract Spaces and Geometries

Mathematics extends the concept of dimensions beyond the physical realm. A mathematical dimension refers to the number of independent coordinates needed to specify a point in a given space. This allows for the exploration of spaces with any number of dimensions, even infinite ones.

-

One-dimensional space: A line is a one-dimensional space. A point on the line can be uniquely identified by a single coordinate (e.g., x = 3).

-

Two-dimensional space: A plane is a two-dimensional space. A point in the plane requires two coordinates (x, y) to specify its position.

-

Three-dimensional space: As discussed earlier, this is the space we experience daily.

-

Higher-dimensional spaces: Mathematics readily handles spaces with four or more dimensions. These are abstract spaces that can't be directly visualized but are crucial for various mathematical applications. They're often represented using coordinate systems or other mathematical structures. For instance, a point in four-dimensional space could be written as (x, y, z, w).

Manifolds and Topology: Beyond Euclidean Spaces

Mathematical spaces aren't always Euclidean (meaning they don't follow the standard rules of geometry we're used to). Manifolds, for instance, are spaces that locally resemble Euclidean spaces but can have a complex global structure. The surface of a sphere is a two-dimensional manifold, but it's not flat like a plane. The "measurement" on a manifold might involve specialized coordinate systems or descriptions based on its intrinsic geometry.

Topology deals with properties of spaces that are invariant under continuous deformations. It concerns connectivity, holes, and other features regardless of the specific shape or metric. Dimensional analysis in topology is more qualitative than quantitative, focusing on the fundamental properties of the space rather than specific coordinate measurements.

Dimensions in Computer Graphics and Data Visualization: Representing Information

In computer graphics, dimensions are used to represent visual data. A 2D image is represented by a grid of pixels arranged along two dimensions (width and height), each pixel having its color information as additional data. 3D graphics add a third dimension (depth), allowing for the creation of realistic-looking objects and scenes. The measurements here are pixel coordinates and associated color values.

Data visualization utilizes dimensions to represent complex datasets. Scatter plots display data points in two or three dimensions, using the data values themselves as the coordinates. Higher-dimensional datasets can be visualized using various techniques, like parallel coordinates or dimensionality reduction algorithms that project the data onto a lower-dimensional space. The “measurement” is the data value corresponding to each dimension being visualized.

Fractal Dimensions: Measuring Irregularity

Fractals are geometric shapes with self-similar patterns at different scales. They possess fractal dimensions that are not necessarily integers. The fractal dimension quantifies the space-filling capacity of a fractal; a higher fractal dimension indicates a more complex and space-filling structure. This “measurement” is derived from mathematical analysis of the fractal's self-similarity properties.

Dimensions in Other Contexts: A Broader Perspective

The concept of dimension extends beyond the scientific and mathematical realms. In philosophy, dimensions can refer to different aspects of reality or experience:

-

Philosophical Dimensions: Some philosophers posit the existence of multiple dimensions of reality, including spiritual, ethical, or temporal dimensions, which are not directly measurable in the physical sense. These dimensions provide frameworks for understanding human experience and the nature of reality.

-

Social Dimensions: In sociology, "dimension" refers to different aspects of social life, such as social class, power, or gender. These are complex constructs, not easily quantifiable, but are crucial for understanding social dynamics.

-

Psychological Dimensions: Psychology might use the term "dimension" to refer to different aspects of personality or cognition. For example, personality traits can be described as lying on various dimensions, allowing for a multi-dimensional representation of an individual's personality.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Concept

The answer to "a dimension is a measurement written as a…" is highly context-dependent. While in physics and mathematics it often involves numerical coordinates or values, in other fields it can represent abstract concepts or qualitative properties. The common thread is that dimensions provide a framework for structuring and understanding complex systems, whether physical, mathematical, or conceptual. Regardless of the context, understanding the concept of dimensionality is crucial for analyzing data, modeling systems, and comprehending the world around us. The ability to represent dimensions appropriately, through numerical coordinates, abstract mathematical constructs, or even qualitative descriptors, is key to progress in various fields. Furthermore, understanding the various types of measurements and their relationships – scalars, vectors, tensors – allows for a deeper appreciation of the intricacies of multi-dimensional analysis.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

One Flew Over The Cuckoos Nest Ch 1 Summary

Mar 17, 2025

-

Monopolistic Competition Is An Industry Characterized By

Mar 17, 2025

-

Summary Of The Book Thief Chapters

Mar 17, 2025

-

Chapter Three Lord Of The Flies Summary

Mar 17, 2025

-

What Colonys Founders Believed That Tolerance Was A Great Virtue

Mar 17, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Dimension Is A Measurement Written As A . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.