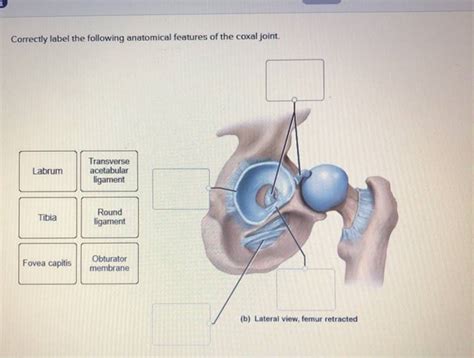

Correctly Label The Following Anatomical Features Of The Coxal Joint

Onlines

Mar 16, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Correctly Labeling the Anatomical Features of the Coxal Joint

The coxal joint, also known as the hip joint, is a ball-and-socket synovial joint formed by the articulation of the head of the femur (thigh bone) and the acetabulum of the hip bone (os coxae). Understanding its intricate anatomy is crucial for anyone studying anatomy, physiotherapy, orthopedics, or any related field. This comprehensive guide will delve into the detailed anatomical features of the coxal joint, providing a thorough explanation for correct labeling. We'll explore the bony landmarks, ligaments, muscles, and associated structures, ensuring you can confidently identify and label each component.

Bony Landmarks of the Coxal Joint

The accurate labeling of the coxal joint begins with a solid understanding of the bony structures involved. Both the femur and the acetabulum contribute significantly to the joint's stability and functionality.

Femur:

-

Head of the Femur: This is the rounded, proximal end of the femur, fitting snugly into the acetabulum. Its smooth, articular surface is crucial for facilitating movement. Note: The fovea capitis is a small pit located on the head of the femur, representing the attachment point for the ligament of the head of the femur.

-

Neck of the Femur: This is the constricted area connecting the head of the femur to the shaft. It's relatively narrow and vulnerable to fractures, particularly in older adults.

-

Greater Trochanter: A large, prominent bony projection located laterally on the proximal femur. It serves as an important attachment site for several hip muscles, playing a crucial role in hip abduction, external rotation, and extension.

-

Lesser Trochanter: A smaller, less prominent bony projection located medially and inferiorly to the greater trochanter. It also serves as an attachment point for several hip muscles.

-

Intertrochanteric Line: A faint ridge running between the greater and lesser trochanters on the anterior surface of the femur.

-

Intertrochanteric Crest: A more prominent ridge located on the posterior surface of the femur, connecting the greater and lesser trochanters.

Acetabulum:

-

Acetabular Fossa: A non-articular depression located in the center of the acetabulum. It’s filled with fat and the transverse acetabular ligament.

-

Articular Surface of the Acetabulum: The smooth, concave surface of the acetabulum that articulates with the head of the femur. This surface is horseshoe-shaped, leaving the acetabular fossa non-articular.

-

Acetabular Labrum: A fibrocartilaginous ring attached to the periphery of the acetabulum. It deepens the socket, increasing stability and congruency of the joint. Important: This labrum enhances the suction seal of the joint, crucial for stability.

-

Acetabular Notch: An indentation located at the inferior aspect of the acetabulum. This notch is bridged by the transverse acetabular ligament.

-

Ilium, Ischium, and Pubis: It's important to remember that the acetabulum itself is formed by the fusion of three bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. While not directly part of the articular surface, understanding this fusion is essential for comprehending the overall structure of the hip bone.

Ligaments of the Coxal Joint

The coxal joint's remarkable stability is significantly attributed to its strong ligamentous structures. These ligaments restrict excessive movement and provide crucial support.

-

Iliofemoral Ligament (Y-ligament): The strongest ligament of the hip joint. Its shape resembles a "Y," with its superior fibers attaching to the anterior inferior iliac spine and its inferior fibers attaching to the intertrochanteric line of the femur. It prevents excessive hyperextension of the hip.

-

Pubofemoral Ligament: Located inferiorly and medially, this ligament runs from the superior pubic ramus and the iliopubic eminence to the neck of the femur. It limits abduction and external rotation.

-

Ischiofemoral Ligament: This ligament is located posteriorly, running from the ischium to the neck of the femur. It limits internal rotation and prevents excessive extension.

-

Ligament of the Head of the Femur: This intracapsular ligament extends from the fovea capitis of the femur to the acetabular fossa. It's relatively weak and carries a small artery that supplies a portion of the femoral head (arteria capitis femoris).

Note: The understanding of the ligaments’ attachments and functions is crucial for comprehending the mechanics of the hip joint and the restrictions placed on its movement.

Muscles of the Coxal Joint

The muscles surrounding the coxal joint contribute significantly to its mobility and stability. These muscles are responsible for a wide range of movements, including flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal rotation, and external rotation.

Several muscle groups contribute to the movement of the coxal joint:

-

Anterior Muscles: These primarily involve hip flexion. Examples include the iliopsoas (iliacus and psoas major), rectus femoris (part of the quadriceps femoris), and sartorius.

-

Posterior Muscles: These mainly involve hip extension, such as the gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus (hamstrings).

-

Medial Muscles: This group is involved in hip adduction. The adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, gracilis, and pectineus are key players.

-

Lateral Muscles: Hip abduction is facilitated by muscles in this group, mainly the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus, along with the tensor fasciae latae.

-

Rotator Muscles: Internal and external rotation of the hip involves a complex interplay of muscles, including the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, piriformis, obturator internus, obturator externus, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and quadratus femoris.

Associated Structures

Beyond the bones, ligaments, and muscles, other structures contribute to the overall function and health of the coxal joint.

-

Synovial Membrane: Lines the interior of the joint capsule, producing synovial fluid, which lubricates the joint and reduces friction.

-

Joint Capsule: A fibrous sac that encloses the entire joint, providing stability and containment for the synovial fluid.

-

Articular Cartilage: A smooth, resilient tissue covering the articular surfaces of the femur and acetabulum. It minimizes friction during movement.

-

Bursae: Fluid-filled sacs located around the joint, reducing friction between tendons and bones. The greater trochanteric bursa is a notable example, often implicated in hip bursitis.

-

Nerves: The coxal joint receives innervation from various nerves, including branches of the lumbar plexus (like the femoral and obturator nerves) and the sacral plexus (like the sciatic nerve). These nerves provide sensory feedback and motor control to the muscles surrounding the joint.

-

Blood Vessels: The arterial supply is primarily through branches of the femoral artery and the internal iliac artery. Venous drainage mirrors the arterial supply.

Clinical Significance: Common Injuries and Conditions

Correctly labeling the anatomical features of the coxal joint is not just an academic exercise. It's essential for understanding common hip injuries and conditions:

-

Hip Dislocation: This involves the head of the femur being forced out of the acetabulum, often requiring immediate medical attention. Understanding the ligaments and their roles helps explain the mechanism of injury.

-

Hip Fractures: These can occur at various points, including the neck, trochanters, or shaft of the femur. Accurate labeling allows for precise description of the fracture location.

-

Hip Bursitis: Inflammation of the bursae around the hip joint, often caused by overuse or trauma, can lead to pain and limited mobility.

-

Osteoarthritis: Degenerative joint disease characterized by the breakdown of articular cartilage, leading to pain, stiffness, and decreased range of motion.

-

Labral Tears: Tears in the acetabular labrum can cause pain, clicking, and instability in the hip joint.

Conclusion

Mastering the accurate labeling of the coxal joint’s anatomical features requires diligent study and a systematic approach. By thoroughly understanding the bones, ligaments, muscles, and associated structures, you gain a fundamental knowledge base for comprehending the complex biomechanics of the hip joint and its clinical implications. This comprehensive guide has provided a detailed roadmap to achieve this understanding, equipping you to confidently identify and label each component. Remember to utilize anatomical models, diagrams, and practical sessions to reinforce your learning and develop a strong anatomical foundation. This will prove invaluable in your chosen field, enabling you to better understand, diagnose, and treat conditions affecting this vital joint.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Which Of The Following Descriptions Best Describes Leadership

Mar 16, 2025

-

3a Polynomial Characteristics Worksheet Answer Key

Mar 16, 2025

-

Domain 3 Lesson 1 Fill In The Blanks

Mar 16, 2025

-

This Poster Shows A Dragon Symbolizing China

Mar 16, 2025

-

Catcher In The Rye Chapter 16 Summary

Mar 16, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Correctly Label The Following Anatomical Features Of The Coxal Joint . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.