Describe The Specific Attributes Of An Experimental Research Design.

Onlines

Mar 27, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Delving Deep into Experimental Research Design: Attributes, Advantages, and Limitations

Experimental research, the gold standard in many scientific fields, stands apart due to its ability to establish cause-and-effect relationships. Unlike observational studies which simply describe correlations, experimental designs actively manipulate variables to observe their impact, providing stronger evidence for causality. However, understanding the specific attributes of a well-designed experiment is crucial for its success and accurate interpretation. This article will delve deep into these attributes, exploring their importance and potential limitations.

Core Attributes of a Robust Experimental Design

Several key attributes define a strong experimental design. These attributes ensure the reliability and validity of the results, minimizing bias and increasing the confidence in the conclusions drawn.

1. Manipulation of the Independent Variable: The Heart of Experimentation

At the core of any experiment lies the manipulation of the independent variable (IV). This is the variable that the researcher controls and changes to observe its effect. It's crucial to clearly define the IV and its different levels or conditions (e.g., treatment vs. control group, different doses of a medication). This controlled manipulation distinguishes experiments from other research designs. Without it, establishing causality is impossible.

For example, in a study investigating the effect of a new teaching method on student performance, the independent variable is the teaching method itself. The researcher would manipulate this variable by assigning different groups of students to either the new method or a traditional method.

2. Measurement of the Dependent Variable: Observing the Outcome

The dependent variable (DV) is the variable being measured to assess the effect of the independent variable. It's the outcome or response that the researcher expects to change as a result of the manipulation. Accurate and reliable measurement of the DV is paramount. This requires careful selection of appropriate measurement tools and procedures to minimize error and ensure consistency.

In our teaching method example, the dependent variable could be students' test scores, their level of engagement in class, or their overall understanding of the subject matter.

3. Random Assignment: The Cornerstone of Internal Validity

Random assignment is a critical attribute that ensures that participants are assigned to different experimental conditions randomly. This minimizes the risk of systematic differences between groups, reducing the influence of confounding variables—variables other than the IV that could affect the DV. Random assignment helps to create equivalent groups at the start of the experiment, increasing the internal validity—the confidence that the observed effect is indeed due to the manipulation of the IV.

Without random assignment, observed differences in the DV might be attributable to pre-existing differences between groups rather than the IV manipulation.

4. Control Group: A Baseline for Comparison

A control group, receiving no treatment or a standard treatment, serves as a benchmark against which the effects of the experimental manipulation can be compared. This provides a baseline for evaluating the impact of the IV. While not always necessary (e.g., in some within-subjects designs), a control group significantly enhances the interpretation of results and strengthens causal inferences.

In our example, the control group would receive the traditional teaching method, allowing researchers to compare its effectiveness with the new method.

5. Replication: Ensuring Reliability and Generalizability

Replication is the ability to repeat the experiment and obtain similar results. Successful replication confirms the reliability and generalizability of the findings. A study that cannot be replicated raises concerns about the validity of its conclusions. Replication can be within the same study (using multiple participants within each group) or across different studies conducted by independent researchers.

Replication helps to rule out the possibility that the initial results were due to chance or other extraneous factors.

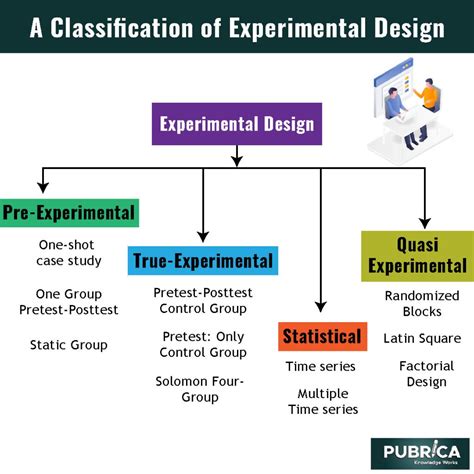

Types of Experimental Designs: A Spectrum of Approaches

Several types of experimental designs exist, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. The choice of design depends on the research question, resources, and ethical considerations.

1. Pre-experimental Designs: Simpler, but with Limitations

These designs lack the rigor of true experimental designs due to the absence of random assignment or a control group. They are often used in exploratory research or when resources are limited. Examples include:

- One-shot case study: A single group is exposed to a treatment, and the outcome is measured. It lacks a control group and pre-test, making causal inferences weak.

- One-group pretest-posttest design: A single group is measured before and after a treatment. While it includes a pre-test, it lacks a control group, making it vulnerable to confounding variables.

2. True Experimental Designs: The Gold Standard

These designs incorporate random assignment and a control group, providing stronger evidence for causality. Examples include:

- Pretest-posttest control group design: Participants are randomly assigned to either an experimental or control group. Both groups are measured before and after the treatment. This design controls for many threats to internal validity.

- Posttest-only control group design: Similar to the pretest-posttest design, but without the pre-test. This simplifies the procedure and reduces participant burden but may make it more challenging to control for pre-existing differences.

3. Factorial Designs: Exploring Multiple Independent Variables

These designs investigate the effects of two or more independent variables simultaneously, allowing researchers to examine main effects (the effect of each IV individually) and interaction effects (how the IVs interact to influence the DV). Factorial designs are particularly useful for understanding complex relationships between variables.

4. Quasi-experimental Designs: When Random Assignment Isn't Possible

These designs resemble true experiments but lack random assignment. This often occurs due to practical or ethical limitations. While they may not provide as strong evidence for causality, they are valuable when random assignment is infeasible. Examples include:

- Nonequivalent control group design: Groups are not randomly assigned, but a comparison group is used.

- Interrupted time series design: Measurements are taken repeatedly before and after an intervention, allowing for an assessment of changes in the DV over time.

Threats to Validity: Potential Pitfalls in Experimental Research

Even with careful design, several factors can threaten the validity of experimental results.

1. Internal Validity: Did the IV Really Cause the Effect?

Threats to internal validity compromise the confidence that the IV caused the observed changes in the DV. Examples include:

- History: External events that occur during the experiment.

- Maturation: Natural changes in participants over time.

- Testing: The act of pre-testing itself influencing subsequent scores.

- Instrumentation: Changes in the measurement instruments or procedures.

- Regression to the mean: Extreme scores tending to move toward the average.

- Selection bias: Systematic differences between groups at the start of the experiment.

- Attrition: Differential loss of participants from different groups.

2. External Validity: Can the Results Be Generalized?

Threats to external validity limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations, settings, or times. Examples include:

- Selection bias: The sample may not be representative of the larger population.

- Setting: The results may only be applicable to the specific setting of the experiment.

- History: The results may be specific to the historical context of the experiment.

- Reactive effects of testing: Pre-testing may sensitize participants to the treatment.

- Multiple treatment interference: Participants receiving multiple treatments simultaneously.

Mitigating Threats to Validity: Strategies for Improvement

Researchers employ several strategies to minimize threats to validity:

- Careful selection of participants: Using representative samples.

- Controlling for extraneous variables: Through randomization, matching, or statistical control.

- Blinding: Preventing participants and/or researchers from knowing which condition participants are in.

- Using multiple measures: Gathering data from multiple sources to corroborate findings.

- Replicating the study: Conducting the experiment multiple times to confirm results.

Conclusion: The Power and Precision of Experimental Research

Experimental research designs, while demanding in terms of planning and execution, offer a powerful approach to understanding causal relationships. By carefully considering the attributes of a robust design, researchers can minimize bias, enhance the reliability and validity of their findings, and contribute significantly to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields. The importance of understanding and addressing potential threats to validity cannot be overstated, ensuring the accuracy and generalizability of research conclusions. A thorough understanding of experimental design is therefore essential for any researcher seeking to establish robust and meaningful cause-and-effect relationships.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

America Story Of Us Episode 7 Cities Worksheet Answers

Mar 30, 2025

-

How Many Chapters In Ready Player One

Mar 30, 2025

-

Chapter 5 Histology Post Laboratory Worksheet Answers

Mar 30, 2025

-

A Hypothetical Organ Has The Following Functional Requirements

Mar 30, 2025

-

A Very Merry Set Of Directions Answer Key

Mar 30, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Describe The Specific Attributes Of An Experimental Research Design. . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.