Exercise 15 Spinal Cord And Spinal Nerves

Onlines

Mar 10, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

Exercise 15: Spinal Cord and Spinal Nerves: A Deep Dive

Understanding the intricate structure and function of the spinal cord and spinal nerves is crucial for anyone studying anatomy, physiology, or related fields. This comprehensive guide delves into the key aspects of Exercise 15, typically found in anatomy and physiology courses, providing a detailed explanation of the spinal cord's anatomy, the organization of spinal nerves, and their clinical significance. We'll also explore common misconceptions and offer practical tips for mastering this complex topic.

The Spinal Cord: Anatomy and Function

The spinal cord, a vital part of the central nervous system (CNS), acts as the primary communication pathway between the brain and the rest of the body. It's a long, cylindrical structure extending from the medulla oblongata of the brainstem to approximately the level of the first lumbar vertebra (L1). Its primary functions include:

- Transmission of nerve impulses: The spinal cord relays sensory information from the periphery to the brain and motor commands from the brain to the muscles and glands. This bidirectional communication is essential for coordinating movement, sensation, and autonomic functions.

- Reflex actions: The spinal cord plays a critical role in mediating reflexes, rapid, involuntary responses to stimuli. These reflexes, such as the knee-jerk reflex, bypass the brain, providing quick protection or responses.

- Locomotion: The spinal cord contributes significantly to the control of rhythmic movements like walking. Central pattern generators within the spinal cord coordinate the alternating activation of muscle groups.

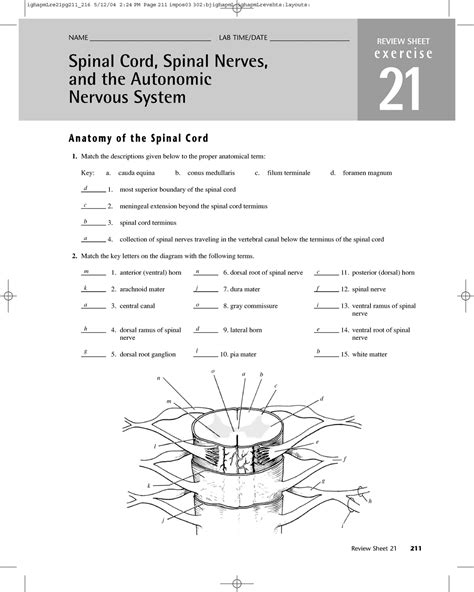

Anatomy of the Spinal Cord: A Detailed Look

The spinal cord’s structure is remarkably organized. Let's break down the key anatomical features:

-

Gray Matter: This butterfly-shaped region in the center of the spinal cord contains neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and unmyelinated axons. It's divided into dorsal (posterior) horns, ventral (anterior) horns, and lateral horns (in the thoracic and upper lumbar regions). The dorsal horns receive sensory information, while the ventral horns contain motor neurons that innervate skeletal muscles. The lateral horns house the cell bodies of the autonomic nervous system.

-

White Matter: Surrounding the gray matter, the white matter consists primarily of myelinated axons organized into ascending (sensory) and descending (motor) tracts. These tracts facilitate the communication between different levels of the spinal cord and between the spinal cord and the brain. Understanding the specific tracts (e.g., corticospinal tract, spinothalamic tract) is vital for comprehending the pathways of sensory and motor information.

-

Meninges: The spinal cord is protected by three layers of connective tissue called meninges: the dura mater (outermost), arachnoid mater (middle), and pia mater (innermost). The subarachnoid space, between the arachnoid and pia mater, contains cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which cushions and nourishes the spinal cord. The knowledge of the meninges is important for understanding lumbar punctures and other clinical procedures.

-

Spinal Cord Segments: The spinal cord is divided into 31 segments, each giving rise to a pair of spinal nerves. These segments are named according to their vertebral level: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 sacral, and 1 coccygeal.

Spinal Nerves: Structure and Function

Spinal nerves are mixed nerves, meaning they contain both sensory and motor fibers. Each spinal nerve arises from the fusion of dorsal and ventral roots.

Dorsal Roots: Sensory Input

The dorsal roots carry sensory information from the body to the spinal cord. Each dorsal root contains the axons of sensory neurons whose cell bodies reside in the dorsal root ganglion. These sensory neurons transmit information about touch, pain, temperature, proprioception (body position), and other sensations.

Ventral Roots: Motor Output

The ventral roots carry motor commands from the spinal cord to the muscles and glands. They contain axons of motor neurons whose cell bodies are located in the ventral horn of the gray matter. These motor neurons innervate skeletal muscles, controlling voluntary movements. They also innervate glands and smooth muscle involved in involuntary functions.

Rami: Branching of Spinal Nerves

After exiting the vertebral column, each spinal nerve divides into several branches called rami:

- Dorsal Ramus: This branch innervates the muscles and skin of the back.

- Ventral Ramus: This branch innervates the muscles and skin of the anterior and lateral body regions. The ventral rami of thoracic nerves form intercostal nerves, while those of other regions form plexuses (complex networks of nerves).

Spinal Nerve Plexuses: A Network of Connections

The ventral rami of cervical, lumbar, and sacral nerves form complex networks called plexuses. These plexuses redistribute the nerve fibers, allowing for a more intricate and flexible innervation of the limbs and other body areas. The major plexuses include:

-

Cervical Plexus: Innervates the neck, shoulders, and diaphragm. The phrenic nerve, a crucial component of this plexus, controls the diaphragm, essential for breathing. Understanding this is crucial for understanding breathing difficulties and related issues.

-

Brachial Plexus: Innervates the upper limbs. Damage to the brachial plexus can result in significant loss of function in the arm and hand. The specific nerves within this plexus (radial, ulnar, median, musculocutaneous) innervate distinct muscle groups. Knowing the innervation pattern is key for diagnosing nerve injuries in the upper limb.

-

Lumbar Plexus: Innervates the anterior thigh and medial leg. The femoral and obturator nerves are major components of the lumbar plexus. Understanding their functions is crucial for diagnosing hip and leg problems.

-

Sacral Plexus: Innervates the posterior thigh, leg, and foot. The sciatic nerve, the largest nerve in the body, is a major component of this plexus. Sciatica, pain radiating down the leg, is often associated with sciatic nerve compression.

Clinical Significance: Understanding Neurological Deficits

Damage to the spinal cord or spinal nerves can result in a range of neurological deficits. The location and extent of the damage will determine the specific symptoms. For instance:

-

Spinal cord injury (SCI): Can cause paralysis, loss of sensation, and autonomic dysfunction. The higher the level of the injury, the more extensive the deficits.

-

Nerve root compression: Can cause pain, numbness, weakness, and other sensory and motor disturbances in the area innervated by the affected nerve root. This can be caused by herniated intervertebral discs, spinal stenosis, or other conditions.

-

Peripheral nerve damage: Can result in specific patterns of sensory and motor loss, depending on the nerve involved. This can be caused by trauma, infection, or other factors. Understanding the precise innervation pattern is key for correct diagnosis.

Mastering Exercise 15: Tips and Tricks

Mastering the complexities of Exercise 15 requires a systematic approach:

-

Visual Learning: Utilize anatomical models, diagrams, and atlases to visualize the three-dimensional relationships between different structures.

-

Active Recall: Test your knowledge frequently using flashcards, practice questions, and self-testing. This active recall strengthens memory consolidation.

-

Clinical Correlation: Relate the anatomical structures to their clinical significance. Understanding the potential consequences of spinal cord and nerve damage enhances comprehension and retention.

-

Mnemonics and Acronyms: Use memory aids to remember the names and pathways of spinal tracts and nerves.

-

Group Study: Discuss the material with classmates, explaining concepts to each other. This collaborative learning method enhances understanding and identifies knowledge gaps.

Common Misconceptions and Clarifications

Several common misconceptions surround the spinal cord and spinal nerves:

-

The spinal cord extends the entire length of the vertebral column: This is false. The spinal cord ends at approximately L1. The nerves continue to travel downwards to the appropriate vertebral levels, forming the cauda equina.

-

All spinal nerves are identical: This is inaccurate. Spinal nerves differ in their innervation patterns, branching, and functions according to their segmental origin (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, coccygeal).

-

Understanding only the gross anatomy is sufficient: While understanding the overall structure is essential, a deeper understanding of the specific tracts, nerves, and their pathways is crucial for mastering this topic.

By understanding the intricate anatomy, physiology, and clinical significance of the spinal cord and spinal nerves, you build a strong foundation for further study in neurology, neurosurgery, and other related healthcare fields. Remember that consistent study, active recall, and clinical correlation are key to mastering this complex yet fascinating system. Through diligent effort and a structured approach, you can confidently tackle Exercise 15 and achieve a thorough understanding of this critical aspect of human anatomy and physiology.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Physical Education 1 Word Search Volleyball Answer Key

Mar 10, 2025

-

Tattoos On The Heart Chapter 1 Summary

Mar 10, 2025

-

Identify The True And False Statements About Color Blind Racism

Mar 10, 2025

-

A Wrinkle In Time Chapter Synopsis

Mar 10, 2025

-

What Is The Theme Of The Cask Of Amontillado

Mar 10, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Exercise 15 Spinal Cord And Spinal Nerves . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.