When The Rope Is Pulled In The Direction Shown

Onlines

Mar 20, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

When the Rope is Pulled: Exploring Tension, Forces, and Mechanical Advantage

Understanding the mechanics of a pulled rope is fundamental to numerous fields, from simple everyday tasks to complex engineering projects. This seemingly simple action – pulling a rope – involves a complex interplay of forces, tensions, and mechanical advantage, the principles of which govern everything from lifting heavy objects with pulleys to understanding the stresses within suspension bridges. This in-depth exploration will delve into the physics behind rope pulling, examining the various scenarios and factors that influence the outcome.

Understanding Tension

At the heart of rope mechanics lies the concept of tension. Tension is the force transmitted through a rope, cable, or other similar flexible connector when it is pulled tight by forces acting from opposite ends. The tension force is always directed along the length of the rope and pulls equally on the objects at both ends. It's crucial to remember that tension is not a property of the rope itself but rather a force acting on the rope. The rope itself simply transmits this force.

Factors Affecting Tension

Several factors influence the tension in a rope:

-

Applied Force: The magnitude of the force applied to the rope directly affects the tension. A larger pulling force results in higher tension.

-

Weight of the Rope: If the rope has a significant weight, its own weight contributes to the tension, particularly in longer ropes or ropes hanging vertically. The tension will be higher at the points closer to the support points.

-

Friction: Friction between the rope and any surfaces it contacts (pulleys, ground, etc.) reduces the effective force transmitted and can impact the tension.

-

Angle of Pull: The angle at which the rope is pulled relative to the horizontal affects the tension. Pulling at an angle requires more force to achieve the same horizontal component of force, thus increasing the overall tension.

-

Elasticity of the Rope: The material properties of the rope influence its response to tension. A more elastic rope will stretch more under the same tension, while a less elastic rope will stretch less.

Simple Rope Pulling Scenarios

Let's explore some common scenarios where understanding rope tension is crucial:

1. Pulling a Single Object Horizontally

Imagine pulling a crate across a frictionless surface using a rope. The tension in the rope is equal to the force applied to the crate (assuming negligible rope mass). If the crate accelerates, Newton's second law (F=ma) applies: the tension equals the mass of the crate multiplied by its acceleration.

2. Pulling a Single Object Vertically

Pulling a weight vertically using a rope introduces the force of gravity. The tension in the rope must overcome the weight of the object (mass x gravity) to lift it. If the object is moving upward at a constant velocity, the tension equals the weight of the object. If it's accelerating upward, the tension will be greater than the weight. If the object is accelerating downward, the tension will be less than the weight.

3. Pulling an Object at an Angle

When pulling an object at an angle, the tension in the rope is greater than the horizontal component of the force needed to move the object. This is because the tension has both horizontal and vertical components, with the vertical component being counteracted by the normal force of the surface or the weight of the object. Resolving the tension into its components (using trigonometry) is essential in understanding the forces involved.

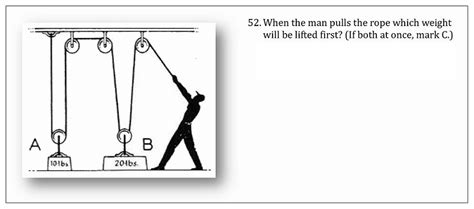

Mechanical Advantage: Pulleys and Systems

The introduction of pulleys significantly alters the dynamics of rope pulling by introducing mechanical advantage. A pulley system allows for lifting heavier objects with less applied force. The mechanical advantage of a pulley system is defined by the ratio of the output force (the weight lifted) to the input force (the force applied to the rope).

Types of Pulley Systems

Various pulley systems exist, each with a different mechanical advantage:

-

Fixed Pulley: A fixed pulley changes the direction of the force but doesn't provide any mechanical advantage. The tension in the rope remains equal to the weight being lifted.

-

Movable Pulley: A movable pulley halves the required input force, giving a mechanical advantage of 2. The tension in the rope is half the weight being lifted.

-

Compound Pulley Systems: Combining fixed and movable pulleys creates more complex systems with greater mechanical advantage. The mechanical advantage is directly related to the number of ropes supporting the load.

Calculating Mechanical Advantage

The mechanical advantage (MA) of a pulley system can be calculated using the following formula:

MA = Number of supporting ropes

This is a simplified calculation and assumes ideal conditions (no friction, massless ropes and pulleys). In reality, friction and the weight of the ropes and pulleys will reduce the effective mechanical advantage.

Advanced Considerations: Rope Dynamics and Material Science

Beyond the basic principles, several more advanced aspects influence rope behavior:

Rope Elasticity and Stretch

Real-world ropes exhibit elasticity, meaning they stretch under tension. This stretch can affect the calculation of tension and mechanical advantage, especially in dynamic scenarios where the load is moving.

Rope Strength and Breaking Point

Every rope has a maximum tensile strength, beyond which it will break. Engineers must account for this limit when designing structures and systems involving ropes. Factors such as material properties, diameter, and age influence the rope's tensile strength.

Dynamic Loading

The way a load is applied to a rope – slowly versus suddenly – impacts the rope's response. Dynamic loading, where the load is applied quickly, can generate significantly higher tension than static loading, increasing the risk of rope failure.

Applications and Real-World Examples

The principles of rope pulling are essential in various fields:

-

Construction: Cranes, hoists, and lifting equipment rely heavily on rope systems to lift heavy materials.

-

Maritime: Ships utilize ropes for mooring, sailing, and other crucial operations.

-

Sports: Climbing, sailing, and many other sports involve the use of ropes under tension.

-

Industrial Applications: Conveyor belts, elevators, and other machinery employ ropes for material handling and movement.

-

Bridge Construction: Suspension bridges utilize massive cable systems to support the bridge deck, with each cable carrying significant tension.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Subject

Understanding "when the rope is pulled" involves far more than a simple intuitive grasp of the action. It requires a thorough understanding of tension, forces, mechanical advantage, and various other factors influencing rope behavior. This knowledge is essential for safe and efficient use of ropes in various applications, from everyday tasks to complex engineering projects. By combining the theoretical principles with practical considerations, we can effectively harness the power and versatility of rope systems. Further exploration into the specific materials used in ropes, advanced pulley systems, and dynamic rope analysis will lead to a more complete understanding of this ubiquitous yet complex element of physics and engineering.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Match Each Satirical Quote To Its Real Meaning

Mar 20, 2025

-

1 7 General Excel Tools For Data Analysis

Mar 20, 2025

-

Enzyme Cut Out Activity Answer Key

Mar 20, 2025

-

The Lord Of The Flies Chapter 4 Summary

Mar 20, 2025

-

Which Statement Best Describes Nutrient Density

Mar 20, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about When The Rope Is Pulled In The Direction Shown . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.