A Model For Circuits Part 2 Potential Difference

Onlines

Mar 23, 2025 · 7 min read

Table of Contents

A Model for Circuits: Part 2 - Potential Difference

This article delves deeper into the fascinating world of electrical circuits, focusing specifically on potential difference, also known as voltage. Building upon the foundational concepts introduced in Part 1 (assuming a prior understanding of basic circuit components and current), we'll explore the crucial role potential difference plays in driving current through a circuit and how it relates to other key circuit parameters. We'll use analogies, practical examples, and clear explanations to solidify your understanding. By the end, you'll have a comprehensive grasp of potential difference and its significance in circuit analysis.

Understanding Potential Difference: The Analogy of Water Flow

Imagine water flowing downhill. The higher the starting point, the greater the potential energy of the water, and the faster it flows. Similarly, in an electrical circuit, potential difference (voltage) is the driving force that pushes electrons through the circuit. It represents the energy difference between two points in a circuit. The higher the potential difference, the greater the "pressure" on the electrons, resulting in a stronger current.

We measure potential difference in volts (V). One volt is defined as one joule of energy per coulomb of charge. This means that a potential difference of one volt will impart one joule of energy to each coulomb of charge as it moves between the two points. This crucial relationship links energy, charge, and voltage:

Energy (Joules) = Charge (Coulombs) x Potential Difference (Volts)

The Battery: The Source of Potential Difference

In most circuits, the source of potential difference is a battery or a power supply. These devices use chemical reactions (in batteries) or electromagnetic principles (in power supplies) to create a difference in electrical potential between their terminals – the positive (+) and negative (-) poles. This difference in potential "pushes" electrons from the negative terminal, through the circuit, and back to the positive terminal.

Measuring Potential Difference: The Voltmeter

To measure the potential difference (voltage) between two points in a circuit, we use a voltmeter. A voltmeter is always connected in parallel across the component or section of the circuit where we want to measure the voltage. Connecting it in series would disrupt the current flow and provide inaccurate readings. Voltmeters have high internal resistance to minimize the current drawn from the circuit being measured, ensuring minimal impact on the circuit's operation.

Potential Difference and Ohm's Law

Potential difference, current, and resistance are intricately linked through Ohm's Law. This fundamental law states:

Voltage (V) = Current (I) x Resistance (R)

This equation highlights the relationship between these three key parameters. If we increase the voltage, the current will increase proportionally (assuming resistance remains constant). Conversely, if we increase the resistance, the current will decrease, assuming the voltage remains constant. Ohm's Law is a cornerstone of circuit analysis and allows us to predict and calculate the behavior of circuits.

Potential Difference in Series and Parallel Circuits

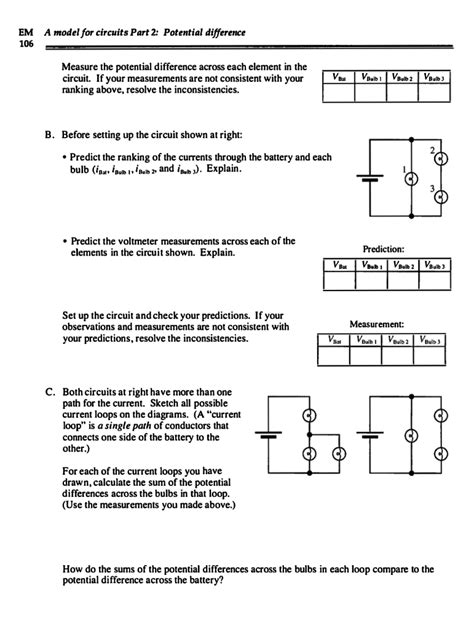

The way potential difference distributes itself in a circuit depends on whether the components are connected in series or parallel.

Series Circuits

In a series circuit, components are connected end-to-end, forming a single path for current flow. The total potential difference across the entire circuit is the sum of the potential differences across each individual component. This means that if you have three resistors in series, with individual voltage drops of V1, V2, and V3, then the total voltage (Vtotal) across the entire series combination is:

Vtotal = V1 + V2 + V3

Parallel Circuits

In a parallel circuit, components are connected side-by-side, providing multiple paths for current flow. In a parallel circuit, the potential difference across each branch is the same as the potential difference across the entire circuit. This is because each component is directly connected to the same two points in the circuit, experiencing the same "electrical pressure."

For example, if a battery provides 12V, each component connected in parallel will see a potential difference of 12V.

Potential Difference and Energy

The potential difference is not just a driving force; it's directly related to the energy transferred to the components in a circuit. As charges move through a component with a potential difference across it, they lose potential energy. This lost potential energy is converted into other forms of energy, such as:

- Heat: Resistors dissipate energy as heat; this is the principle behind incandescent light bulbs.

- Light: Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) convert electrical energy into light.

- Mechanical energy: Motors convert electrical energy into mechanical work.

- Sound: Speakers convert electrical energy into sound waves.

The amount of energy transferred is directly proportional to the potential difference, the charge, and the time:

Energy (Joules) = Potential Difference (Volts) x Charge (Coulombs) = Power (Watts) x Time (Seconds)

This equation emphasizes the crucial role potential difference plays in determining the energy consumed or converted by a circuit component.

Practical Applications of Potential Difference

Understanding potential difference is fundamental to a wide range of applications. Here are just a few examples:

- Power grids: High-voltage power lines efficiently transmit electricity over long distances. Step-down transformers reduce the voltage to safer levels for domestic use.

- Electronic devices: The operation of transistors, integrated circuits, and other electronic components relies heavily on precise control of potential differences.

- Medical equipment: Various medical devices, such as pacemakers and electrocardiograms (ECGs), use potential differences to monitor and control biological processes.

- Sensors: Many sensors, such as thermocouples (which measure temperature) and photodiodes (which measure light intensity), generate a potential difference proportional to the physical quantity being measured.

Potential Difference and Kirchhoff's Laws

Kirchhoff's laws are essential tools for analyzing complex circuits. They build upon the concept of potential difference:

-

Kirchhoff's Voltage Law (KVL): The sum of the potential differences around any closed loop in a circuit is zero. This law essentially states that the energy gained by charges moving through the power source is exactly balanced by the energy lost across the various components in the loop.

-

Kirchhoff's Current Law (KCL): The sum of the currents entering a junction (node) in a circuit equals the sum of the currents leaving that junction. This reflects the conservation of charge; charge cannot be created or destroyed within the circuit.

Understanding KVL and KCL, coupled with a solid grasp of potential difference, allows for the complete analysis of even the most intricate circuit networks.

Troubleshooting Circuits Using Potential Difference Measurements

A voltmeter is a vital tool for troubleshooting electrical circuits. By systematically measuring the potential difference across different components, you can pinpoint the location of faults. For instance:

- Open circuits: If there's an open circuit (a break in the conducting path), the potential difference across the open section will be equal to the total voltage of the source.

- Short circuits: A short circuit (an unintended low-resistance path) will result in a very low potential difference across the components in that branch, while the current might be excessively high.

- Faulty components: If a component has failed (e.g., a resistor has burned out), the potential difference across it might be significantly different from its expected value.

Beyond the Basics: Advanced Concepts

This article provides a solid foundation in understanding potential difference. Further exploration into more advanced concepts could include:

- Capacitance: The ability of a capacitor to store electrical energy due to a potential difference across its plates.

- Inductance: The ability of an inductor to store energy in a magnetic field generated by the current flow, influencing the potential difference.

- AC circuits: Circuits that use alternating current (AC), where the potential difference changes periodically.

- Transient analysis: Analyzing how potential differences and currents change over time in response to changes in the circuit.

Conclusion

Potential difference, or voltage, is the driving force behind the flow of charge in an electrical circuit. Understanding its role in conjunction with Ohm's Law, Kirchhoff's Laws, and the concept of energy conversion is crucial for comprehending circuit behavior and troubleshooting. This article has provided a comprehensive overview, using analogies and practical examples to illustrate the key concepts. By mastering these principles, you'll be well-equipped to analyze and design a wide range of electrical circuits. Remember to continue learning and exploring the fascinating world of electronics; the possibilities are endless.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Exercise 9 5 Making A Topographic Map

Mar 25, 2025

-

Terry Sees A Post On Her Social Media Feed

Mar 25, 2025

-

Access To Healthy Food Research Gmos Note Catcher

Mar 25, 2025

-

Symbolic Interactionists Have Come To The Conclusion That

Mar 25, 2025

-

A Teacher Is One Who Guides Or Leads

Mar 25, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about A Model For Circuits Part 2 Potential Difference . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.