Ac Theory Level 2 Lesson 3

Onlines

Mar 15, 2025 · 5 min read

Table of Contents

AC Theory Level 2: Lesson 3 - Power in AC Circuits

This lesson delves into the complexities of power calculations within alternating current (AC) circuits. Understanding power in AC circuits is crucial for anyone working with electrical systems, from designing efficient circuits to troubleshooting power-related issues. Unlike DC circuits, where power is simply the product of voltage and current, AC circuits introduce the concept of power factor, which significantly impacts the actual power consumed.

Understanding AC Power: Beyond Volts and Amps

In DC circuits, power (P) is calculated straightforwardly as the product of voltage (V) and current (I): P = VI. However, in AC circuits, the relationship is more nuanced due to the sinusoidal nature of voltage and current waveforms. The instantaneous power in an AC circuit fluctuates constantly, making a simple multiplication of voltage and current insufficient for determining the average power consumed over time.

Apparent Power (S): The Overall Power

Apparent power (S) represents the total power seemingly supplied to the circuit. It's calculated as the product of the RMS (Root Mean Square) voltage (V<sub>RMS</sub>) and the RMS current (I<sub>RMS</sub>):

S = V<sub>RMS</sub> * I<sub>RMS</sub>

Apparent power is measured in volt-amperes (VA). It's important to remember that apparent power doesn't represent the actual power used by the load; it only indicates the total power supplied by the source.

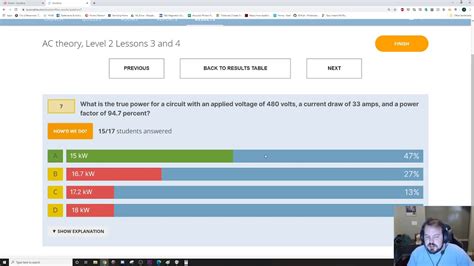

True Power (P): The Actual Power Consumed

True power (P), also known as real power or active power, represents the actual power consumed and converted into useful work by the load. Unlike apparent power, true power accounts for the phase difference between voltage and current. This phase difference is crucial and is directly related to the load's impedance.

P = V<sub>RMS</sub> * I<sub>RMS</sub> * cos(θ)

where θ is the phase angle between the voltage and current waveforms. True power is measured in watts (W).

Reactive Power (Q): Power that Oscillates

Reactive power (Q) represents the power that oscillates between the source and the load without being converted into useful work. This power is associated with energy storage elements like inductors and capacitors. It's calculated as:

Q = V<sub>RMS</sub> * I<sub>RMS</sub> * sin(θ)

Reactive power is measured in volt-amperes reactive (VAR). While not directly contributing to useful work, reactive power is essential for the operation of inductive and capacitive loads.

The Power Triangle: Visualizing AC Power

The relationship between apparent power, true power, and reactive power can be visually represented using the power triangle:

- Hypotenuse: Represents apparent power (S)

- Adjacent side: Represents true power (P)

- Opposite side: Represents reactive power (Q)

The angle θ between the true power and apparent power represents the power factor angle. This triangle is a crucial tool for understanding the power relationships in AC circuits.

Power Factor: The Efficiency Factor

The power factor (PF) is the cosine of the phase angle (θ) between the voltage and current waveforms:

PF = cos(θ) = P / S

The power factor ranges from 0 to 1. A power factor of 1 indicates that the voltage and current are in phase (purely resistive load), meaning all the supplied power is converted into useful work. A power factor less than 1 indicates a phase difference, implying that some of the supplied power is reactive power, not contributing to useful work.

A low power factor is generally undesirable because it means the power source needs to supply more current to deliver the required true power. This leads to increased energy losses in the transmission lines and increased operating costs.

Improving Power Factor

Low power factor can be improved using power factor correction (PFC) techniques. These techniques involve adding capacitor banks to the circuit to compensate for the reactive power produced by inductive loads (like motors). By adding capacitors, the reactive power is reduced, bringing the power factor closer to unity (1), increasing efficiency.

Different Types of Loads and their Impact on Power Factor

The type of load significantly influences the power factor.

Resistive Loads:

Resistive loads, such as incandescent light bulbs and heaters, have a power factor of 1. The voltage and current are in phase, and all the supplied power is converted into heat.

Inductive Loads:

Inductive loads, such as motors, transformers, and inductors, generally have a lagging power factor (less than 1). The current lags behind the voltage. This is because inductors store energy in a magnetic field, which delays the current flow.

Capacitive Loads:

Capacitive loads, such as capacitors themselves, usually have a leading power factor (less than 1). The current leads the voltage. This is because capacitors store energy in an electric field, causing the current to lead the voltage.

Practical Applications and Examples

Understanding power in AC circuits is vital in numerous applications:

-

Electrical System Design: Engineers use power calculations to design efficient and reliable electrical systems, ensuring sufficient power is available for all loads while minimizing losses.

-

Motor Control: Power factor correction is essential for efficient motor operation, improving energy efficiency and reducing operating costs.

-

Power Distribution: Power companies constantly monitor and adjust power factors to optimize power distribution and reduce transmission losses.

-

Troubleshooting Electrical Systems: Analyzing power factors helps diagnose and troubleshoot power-related issues in electrical systems.

Beyond the Basics: Further Exploration

This lesson provides a foundational understanding of power in AC circuits. For a more advanced understanding, consider exploring topics such as:

- Complex Power: Using complex numbers to represent voltage, current, and impedance for a more comprehensive analysis of AC power.

- Three-Phase Power Systems: Extending the concepts of power calculation to three-phase systems, which are commonly used in high-power applications.

- Power Factor Correction Techniques: Deep dive into different PFC methods, including the calculation and selection of appropriate capacitor banks.

- Non-linear Loads and Harmonic Analysis: Understanding the impact of non-linear loads (like rectifiers) on the power system and how to mitigate harmonic distortion.

Conclusion

Mastering the concepts of apparent power, true power, reactive power, and power factor is critical for anyone working with AC circuits. This knowledge enables efficient system design, troubleshooting, and optimization of energy usage. By understanding the power triangle and the impact of different load types, you can effectively manage power in AC circuits and contribute to more efficient and sustainable electrical systems. Further exploration into the more advanced concepts mentioned will solidify your understanding and prepare you for more complex scenarios in the world of electrical engineering.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Exercise 12 Review Sheet Art Labeling Activity 1

Mar 15, 2025

-

Genetic Science Learning Center Answer Key

Mar 15, 2025

-

Software Lab Simulation 12 2 Install Hyper V Configure And Create Vm

Mar 15, 2025

-

The Bible Is Most Adequately Described As

Mar 15, 2025

-

The Spirit That Catches You Sparknotes

Mar 15, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Ac Theory Level 2 Lesson 3 . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.