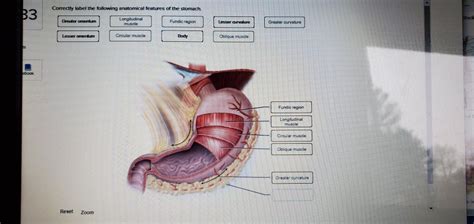

Correctly Label The Following Anatomical Features Of The Stomach

Onlines

Mar 14, 2025 · 6 min read

Table of Contents

Correctly Labeling the Anatomical Features of the Stomach: A Comprehensive Guide

The stomach, a vital organ in the digestive system, is a fascinating and complex structure. Understanding its anatomy is crucial for anyone studying biology, medicine, or related fields. This comprehensive guide will delve into the intricacies of the stomach's anatomy, providing detailed descriptions and clear explanations to help you correctly label its various features. We'll go beyond simple labeling, exploring the functions of each part and their interrelationships within the digestive process.

Major Anatomical Regions of the Stomach

The stomach isn't simply a sac; it's a highly specialized organ with distinct regions, each playing a crucial role in digestion. These regions are characterized by variations in their structure, thickness, and function. Let's explore them in detail:

1. Cardia

The cardia is the most superior (uppermost) part of the stomach. It's the region where the esophagus joins the stomach, forming the cardiac orifice. This orifice is crucial as it acts as a valve, regulating the flow of food from the esophagus into the stomach. The cardia itself is a relatively small region, but its strategic location makes it vital for the digestive process. It's characterized by a slightly constricted structure which helps prevent stomach acid from refluxing into the esophagus.

2. Fundus

Located superior to the cardia and slightly to the left, the fundus is the dome-shaped portion of the stomach. It's often filled with gas, especially after eating. This gas is largely swallowed air that becomes trapped in this region. The fundus's shape and position help to temporarily store ingested food. It also plays a role in the initial mixing of food with gastric juices. Although primarily a storage area, its involvement in early digestion should not be overlooked.

3. Body (Corpus)

The body or corpus represents the largest part of the stomach. This region extends from the fundus to the pylorus. The body's thick muscular walls are responsible for churning and mixing the food with gastric secretions, initiating the process of mechanical digestion. The intense mixing action in the body ensures thorough exposure of the food bolus to the gastric enzymes and acid, preparing it for further breakdown in the intestines. The lining of the body is where most gastric glands are located, actively producing gastric juice.

4. Pylorus

The pylorus is the funnel-shaped distal part of the stomach that connects to the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). The pylorus consists of two sections: the pyloric antrum (wider portion) and the pyloric canal (narrower portion). The pyloric sphincter, a muscular ring at the end of the pyloric canal, controls the release of chyme (partially digested food) into the duodenum. This sphincter plays a crucial role in regulating the rate of gastric emptying. The pyloric region is vital for controlling the pace of digestion, ensuring that only appropriately processed chyme enters the small intestine.

Curvatures and Surfaces of the Stomach

Besides the distinct regions, the stomach also has specific curvatures and surfaces that contribute to its overall shape and function:

1. Lesser Curvature

The lesser curvature is the concave medial border of the stomach. It's shorter than the greater curvature and forms a relatively sharp curve. The lesser curvature is associated with the lesser omentum, a double layer of peritoneum connecting the stomach to the liver.

2. Greater Curvature

The greater curvature is the convex lateral border of the stomach. This is the longer curve and represents the outwardly facing arc of the stomach. The greater curvature is significantly longer than the lesser curvature and attaches to the greater omentum, a large, apron-like fold of peritoneum that hangs down from the greater curvature, contributing to the overall protective function of the abdominal organs.

3. Anterior and Posterior Surfaces

The stomach also has an anterior and a posterior surface. The anterior surface faces forward, lying against the diaphragm and abdominal wall. The posterior surface faces backward, contacting other abdominal structures like the pancreas, spleen, and left kidney. This positioning highlights the stomach's central role within the abdominal cavity and its close proximity to other vital organs. The relationship between the stomach and its neighboring organs is crucial in understanding the impact of gastric issues on the rest of the digestive system.

Microscopic Anatomy: Gastric Glands and Secretions

The inner lining of the stomach, the mucosa, contains millions of gastric glands. These glands are responsible for producing the gastric juice, a mixture of:

1. Hydrochloric Acid (HCl):

HCl creates an extremely acidic environment within the stomach (pH around 1-2). This acidity is essential for:

- Activating pepsinogen: Pepsinogen is an inactive enzyme that's converted to the active form, pepsin, by HCl. Pepsin is a crucial enzyme for protein digestion.

- Killing ingested bacteria: The highly acidic environment effectively kills most bacteria and other harmful microorganisms ingested with food.

- Denaturing proteins: HCl breaks down the complex three-dimensional structures of proteins, making them more accessible to pepsin.

2. Pepsinogen:

This inactive precursor is converted into pepsin by HCl. Pepsin is an endopeptidase, meaning it breaks down proteins within the peptide chain, cleaving them into smaller peptides.

3. Intrinsic Factor:

This glycoprotein is crucial for the absorption of vitamin B12 in the ileum (the terminal part of the small intestine). Vitamin B12 is essential for red blood cell production and neurological function. A deficiency can lead to pernicious anemia.

4. Gastrin:

This hormone is produced by G cells in the antrum of the stomach. Gastrin stimulates the secretion of HCl and pepsinogen, thereby promoting gastric activity and digestion.

5. Mucus:

The stomach lining also produces mucus, a protective layer that prevents the highly acidic gastric juice from digesting the stomach wall itself. The mucus layer is vital to prevent ulcers and other damaging conditions.

Clinical Significance: Understanding Gastric Disorders

A thorough understanding of stomach anatomy is crucial for diagnosing and treating various gastric disorders. These include:

- Gastritis: Inflammation of the stomach lining, often caused by infection, alcohol abuse, or NSAID use.

- Peptic Ulcers: Sores in the stomach or duodenal lining, typically caused by Helicobacter pylori infection or prolonged NSAID use.

- Gastric Cancer: A malignant tumor of the stomach lining, often linked to diet, infection, and genetics.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Chronic reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus, causing heartburn and other symptoms.

Accurate identification of the stomach's different parts is essential in pinpointing the location of these conditions. Imaging techniques like endoscopy and X-rays, coupled with a deep knowledge of stomach anatomy, allow physicians to accurately diagnose and manage these ailments.

Conclusion: Mastering Stomach Anatomy

Correctly labeling the anatomical features of the stomach requires a detailed understanding of its different regions, curvatures, and the functions of its microscopic components. From the cardia, fundus, and body to the pylorus, each region plays a specific role in the complex process of digestion. Understanding the microscopic anatomy, specifically the gastric glands and their secretions, further elucidates the mechanisms of chemical digestion. This knowledge is not only essential for biological and medical studies but also fundamental for understanding and treating various gastric disorders. By mastering the anatomy of the stomach, you gain a deeper appreciation for the intricacies of the human digestive system and its vital contribution to overall health. This guide provides a solid foundation for further exploration of this remarkable organ and its critical role in human physiology. Remember to consistently review and reinforce your learning to fully grasp the complex, yet fascinating, anatomy of the stomach.

Latest Posts

Latest Posts

-

Ati Swift River Simulations 2 0 Client Report Sheet

Mar 14, 2025

-

How Do You Become A Savvy And Sophisticated Digital User

Mar 14, 2025

-

Focused Exam Abdominal Pain Shadow Health

Mar 14, 2025

-

Match The Psychological Perspective To The Proper Description

Mar 14, 2025

-

Activity 3 1 3 Flip Flop Applications Shift Registers Answer Key

Mar 14, 2025

Related Post

Thank you for visiting our website which covers about Correctly Label The Following Anatomical Features Of The Stomach . We hope the information provided has been useful to you. Feel free to contact us if you have any questions or need further assistance. See you next time and don't miss to bookmark.